It was a quiet morning. I had drawn the curtains tightly, so the room was dim and utterly still. Worn out from work, I wanted to give my body a proper rest, so I closed my eyes once more beneath the covers and took a deep breath. I could hear almost nothing—only, faintly, the sound of a Hankyu train passing by, as if it were running somewhere farther away than usual. About thirty minutes later, I looked at my phone. My sleep time was six hours and fifty minutes. Well, that’s about right. Come to think of it, the weather forecast on television yesterday had said it might snow today. From experience, I knew that when snow accumulates, sounds lose their echo and the world grows quieter. Could it be… I got out of bed and opened the curtains. Before me spread the streets of Tonda, blanketed in white, with large flakes of snow drifting down.

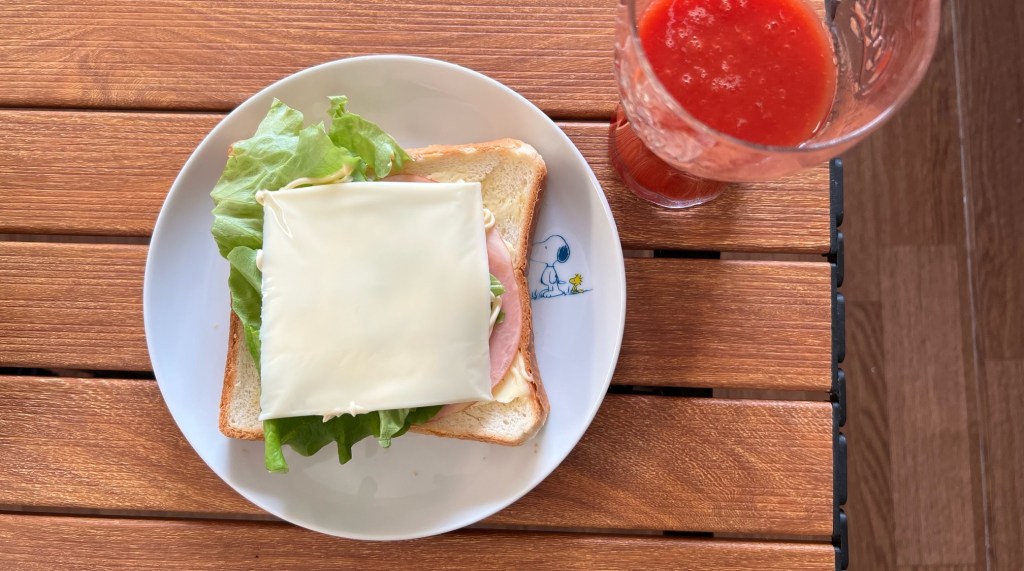

The room, surprisingly, was not all that cold, but it was too chilly to stay barefoot, so I quickly pulled on thick socks and turned on the heater. I brushed my teeth and shaved. Since I had run out of lettuce, I settled for bacon and eggs and a bowl of miso soup for breakfast.

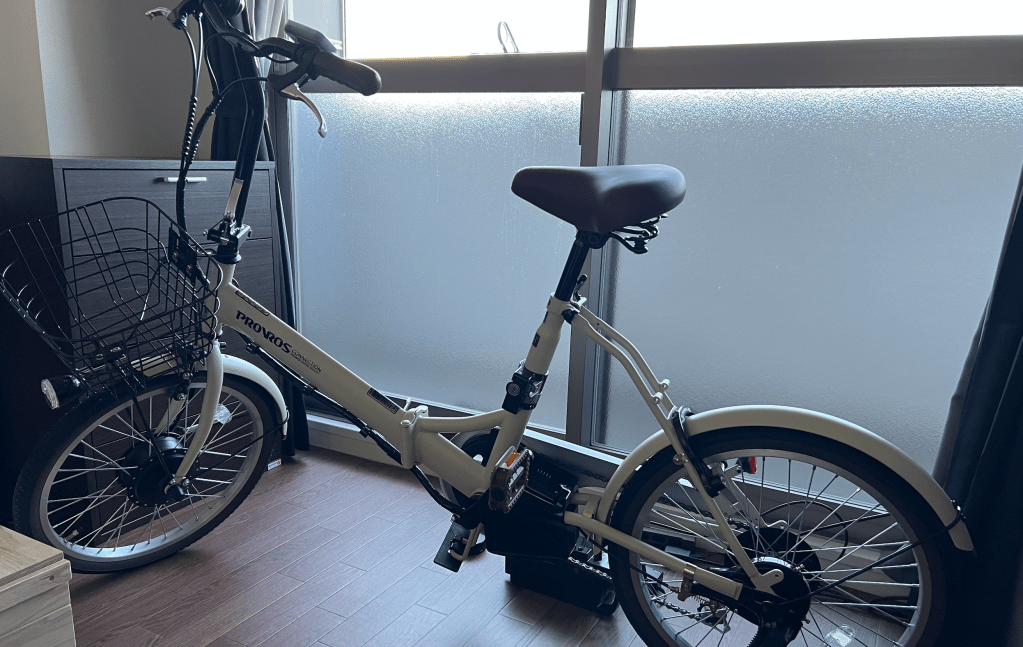

As I made coffee and relaxed in the room, the delivery driver rang my doorbell. The electric-assist bicycle I had ordered the other day had arrived. I had been debating whether to buy it for quite some time. I use my motorcycle for longer trips, but company rules don’t allow me to commute by bike. My commute is a fifteen-minute walk one way, which in winter is just enough to warm me up. But walking under the blazing summer sun is almost dangerous, and I had been wondering what to do about it. Toward the end of summer, I checked several suitable models on Amazon and put one in my cart. Still, owning both a motorcycle and a bicycle felt wasteful, and I never went through with the purchase. So why did I buy it now? Because the owner of the motorcycle parking lot had told me to remove the box where I kept my bike cover. I tried to explain that I couldn’t very well carry the cover on my shoulder every time I rode, but he wouldn’t listen. Other users, he said, came to the lot by bicycle, put the cover in the bike’s basket, and swapped the bicycle for their motorcycle. Apparently, leaving a box was not allowed, but leaving a bicycle with a basket was. What a ridiculous rule, I thought—yet, in a tipsy moment over an evening drink, I ended up buying the bicycle that had been sitting in my Amazon cart. The next morning I came to my senses and regretted pressing the purchase button, but it was a model I had agonized over and chosen months ago, so I found myself thinking, Well, maybe this is fine.

The delivery driver brought a large cardboard box up to my sixth-floor apartment on a dolly.

“It looks like a bicycle. Where would you like it?”

Since it was snowing, I didn’t feel like leaving it outside.

“Ah, inside the room, please,” I said.

I had chosen a small, foldable model, but once it was inside, it turned out to be bigger than I expected. The driver and I carried it together just inside the door.

“It’s cold today. Thanks for coming all this way, even with the bad footing.”

“No problem. Thank you very much,” he said with a smile, and hurried off.

Delivering packages on a day like this must be tough. It’s hard work. I remembered my own days in college, when I worked part-time delivering packages during the year-end gift season. Back then I weighed less than sixty kilos, but my abs were defined, and my chest and arms were strong. Now, even though I’ve lost some weight, compared to those days I’m heavier—and yet my muscle has faded. I hope this bicycle will help me regain some of my strength.

Outside, the snow was still falling steadily. The room was dark, so I turned on a warm-colored light. I began to unpack the large cardboard box little by little. Inside, the beige frame was folded and carefully wrapped. I cut away the packaging piece by piece with scissors. The saddle was the color of tanned leather, the handlebar black, and the grips brown. The pedals, too, were made of brown resin. Centered on beige, the bicycle was balanced nicely with black and brown accents. Sipping the coffee I had brewed earlier that morning, I assembled it bit by bit.

From time to time, I looked out the window. The snowflakes grew larger, then smaller. In the quiet, I worked alone, reading the instructions and turning screws, and I began to picture myself riding this bicycle through the streets of Tonda. With this, it will be easier to go to the big supermarket a little farther from the office. Shopping on the way home from work should be easier too, with a basket. Maybe it makes sense to use the bicycle for commuting and the motorcycle for tennis school. Well, I’ll see how it goes, I thought, letting my mind wander.

Life is a series of choices. Half in resignation, perhaps, I chose the bicycle this time. With that, my life will change a little again. Before I knew it, the assembly was finished. Bicycles these days are well made. The chain had just the right amount of grease, the tires felt properly inflated, and the brakes worked well. When I was done, I started charging the battery.

I looked out the window. The snow was still falling. It doesn’t look like I’ll be riding it today. Imagining the future day when I will place my foot on those pedals, I took another sip of coffee from the pot.